This is Part 2 of a four-part series of posts based on the book “Designing for the Museum Visitor Experience” by Tiina Roppola. Go to Part 1.

Resonating: features that attract and repel visitors

In interviews, visitors often described feeling “drawn to” particular exhibition environments and displays. Roppola uses the concept of resonance to characterise this interaction between visitors and features of the exhibition environment. In physics, ‘resonance’ is used to describe the amplification effect observed when two bodies vibrate at the same wavelength. Similarly, visitors and exhibits can be considered as being in a resonant relationship when they are ‘in tune’ with one another.

Certain environmental features, such as “size, beauty, colour, light, a quality of realism, sensory change/movement and opportunity for action” (Roppola, 2012, p. 126) tend to attract visitors and draw them in. Spatial characteristics can also be resonant – environments that feel pleasant to be in owing to characteristics such as light, spaciousness or aesthetic appeal.

Perceptual resonance

Resonance can be achieved by the way that sensory cues of exhibits interact with our perceptual systems. Sensory cues can be seen as “bottom up” data, which we interpret using “top down” mental constructs – an example is how we readily interpret two dots and a curved line as a smiley face (see below). This process of “filling in” the gap between bottom up sensory data and top down constructs can happen within one sense or between multiple senses (eg. visual cues working with auditory information to create an integrated whole).

Exhibits can take advantage of this intrasensory augmentation to create an enhanced sense of realism – for instance simulator exhibits combine immersive visual stimuli with a relatively modest amount of movement to create a feeling of flying or being in motion. In immersive exhibits or recreated environments, sound effects and smell can be used to enhance realism by hinting at the presence of things unseen – such as bread baking in an oven or the faint cry of a child in the distance. However, simply combining sounds, sights, smells and textures does not automatically create a coherent perceptual whole; the sensory information needs to be congruent with the top-level mental constructs through which visitors interpret them.

Coalescent resonance and how visitors define “interactivity”

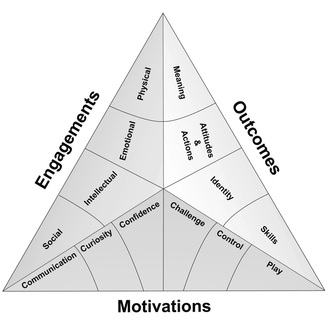

Coalescent resonance occurs when two separate entities come together to form a complementary whole. In an exhibit context, this can mean feeling “part of” the exhibition environment: “visitors can physically, personally and socially interact with, or feel part of, exhibition environments” (Roppola p. 151, original emphasis). Physical coalescence can be literal, such as being able to directly touch or get up close to exhibits; it can also be conceptual as visitors are encouraged to imagine themselves in a given setting or scenario.

Interestingly, Roppola describes several instances where visitors use the term “interactive” in a sense that is very different from the way exhibit designers and other museum professionals use it – namely, that an “interactive” exhibit is one that visitors physically touch or manipulate in some way. This prerequisite seemed less important to visitors, who also used the word “interactive” to pertain to exhibits that allowed physical proximity or social interaction, but not necessarily hands-on contact. A museum professional may call this latter type of exhibit “immersive” rather than “interactive” [1]. This different understanding of the term “interactive” shows the value of qualitative research in validating the terminology we use – when people say they want more “interactive” experiences, do they mean what we’ve assumed they mean?

Impeding Resonance

Just as environmental stimuli can enhance a resonant relationship between visitors and exhibits, they can also impede it. Things that can impede or block resonant experiences:

- “You can only take so much in” – a museum visit can saturate your sensory and cognitive capacities. Visitors deploy strategies to allocate their time and mental budgets according to their interests. A sense of “too much to take in” can be overwhelming and prevent visitors from engaging with an exhibition.

- “It’s all jumbled”- the sense of there being too much to take in can be exacerbated by the lack of a clear order or logic with which to make sense of an exhibit. The ‘signal’ of an interpretive message is lost in the ‘noise’ of an overly cluttered display – different features compete and cancel each other out.

- “The people I’m with won’t let me” – visitors might spend less time on an exhibit than they would like if they feel they’re being hurried along by their companions. Queues and crowding can impede resonance by getting in the way or making an environment less pleasant by their presence.

Next week – Channelling

[1] In my own research, I found that “immersive” was not a word that resonated particularly with visitors when asked to describe exhibit environments. I used the word in my pilot questionnaire and several visitors said they didn’t know what the word meant (and the pilot results suggested these people were just the tip of the iceberg). Given the amount of museological discourse there currently is around “immersive experiences”, this is a point worth noting – we’re potentially talking about visitor experiences in terms visitors would not recognise.